Die Zeit Article

After reading the Zeit article “CO2 certificates: green in disguise” by Tin Fischer and Hannah Knuth I went to Elias Ayrey’s Youtube profile and watched his videos. As an intro, he created an explainer video called “Forest carbon basics”.

On the one hand the Zeit article is very worth reading (unfortunately only readable with a subscription. Tip: create a trial subscription) and at the same time scary. Greenwashing is a massive problem and is used by large corporations to present themselves as “climate neutral”. In the article, the reader learns why this is all fake and lies.

On the other hand, the video of Elias is very good to understand why trees and forests are so extremely important to hold CO2. I have extracted the text and translated it into German because I want to make it accessible to people who are not so confident in English.

Video Forest carbon basics (Transkription)

Hi, my name is Elias Ari, I have years of experience in the forest carbon industry, and I have a PhD in forest remote sensing, which admittedly is a pretty small niche.

I wanted to make these videos to explain how forest carbon projects work. They can be fiercely complicated, they’re very different from one another, and frankly, a lot of the time people cheat.

But before we get into the nitty-gritty details of how people cheat these projects, I want to talk about how trees actually sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

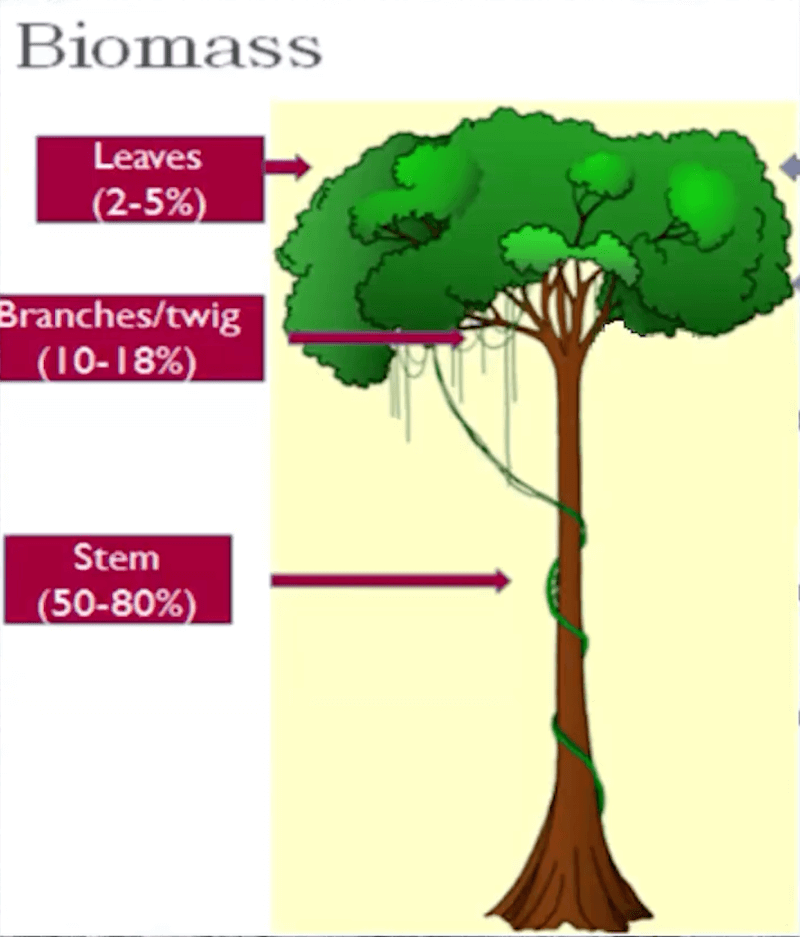

By weight, a tree is 95% wood, the other 5% are leaves, and wood itself is 50% carbon. The other 50% is just hydrogen.

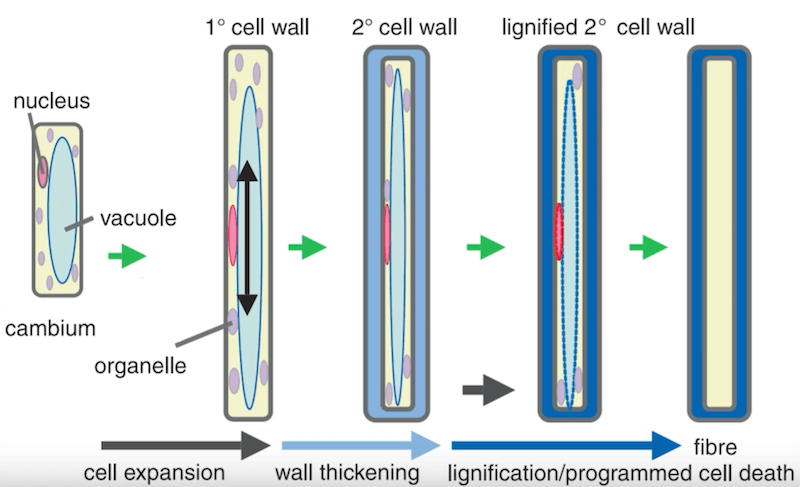

Unlike other living cells, wood cells can kind of be thought of in the same way that you can think of human bone. It’s kind of alive, but it’s kind of not. And the reason for this is that the only purpose of wood is to keep the tree upright, keep the leaves up in the canopy, and to transport water from the roots up to the leaves.

And so to do these two things, wood doesn’t entirely need to be alive. The tree doesn’t want to keep its most precious nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus locked up in wood. And so what the tree does every time it creates new wood cells is evacuate the organelles out of those cells, the DNA, the organelles like mitochondria, and proteins. And all that’s left is a hollow husk that’s essentially just a hollow tube to bring water up to the leaves.

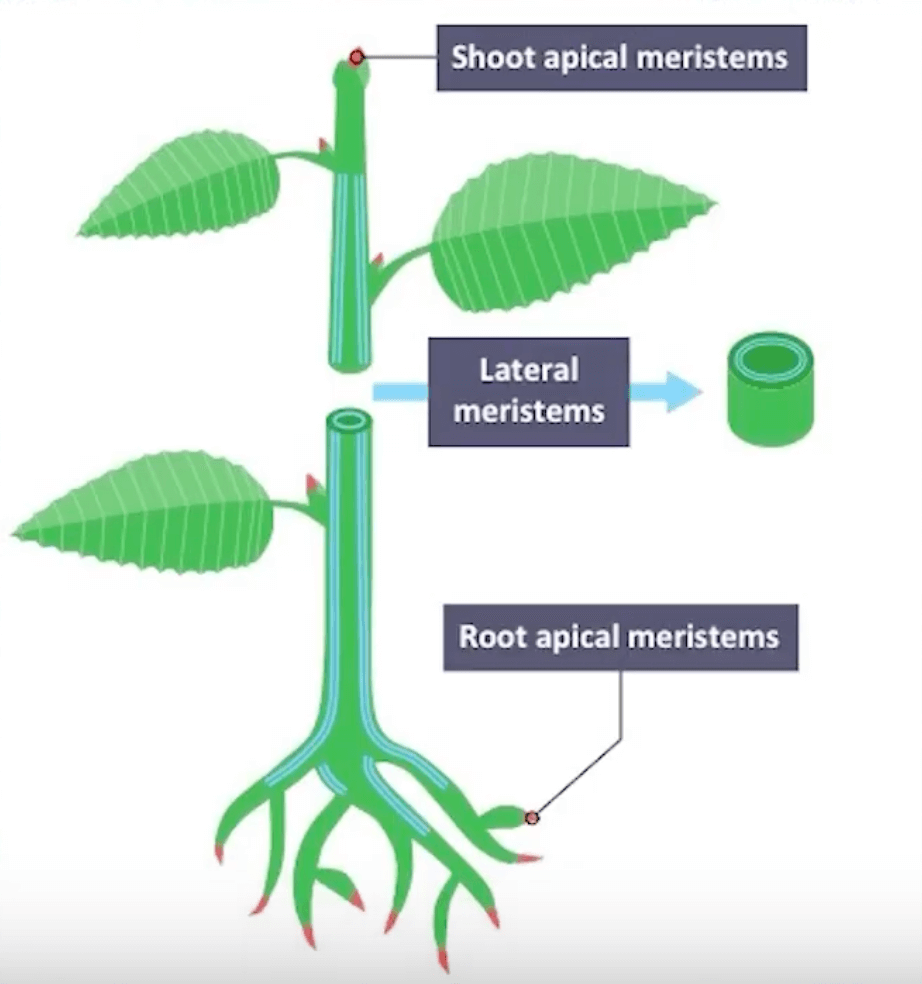

In fact, really the only kind of living parts of the trees are the leaves, meristems at the very tips of the branches, and the cambium, which exists between the bark of the tree and the actual wood. And the cambium is responsible for building out more wood cells.

So where does wood actually come from? Well, as we said, it’s mostly carbon. Trees themselves, they may come from the ground, but most of the material that makes up a tree comes from the atmosphere. It’s CO2.

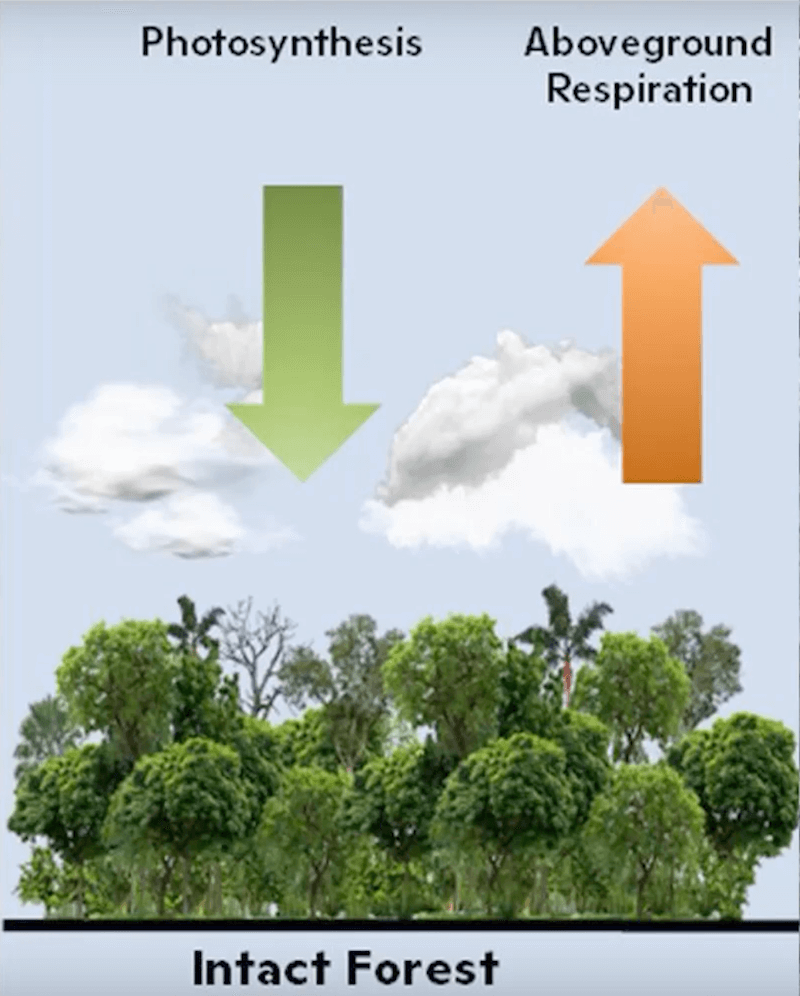

And so we’ve all heard about this process called photosynthesis. Trees take CO2 out of the atmosphere. They combine that with water from the ground using energy from the sun, and they create sugars. And of course, these sugars feed the tree. They’re the food for treats and for the animals that eat the trees.

But an important step here that’s often left out of middle school photosynthesis is that trees, of course, need to break down these sugars again in order to crack the energy out of it. And so just like human beings, trees respire. They will break down their own sugars and release CO2. And so over the course of a day, for all the CO2 that’s going into a tree, almost all of it goes right back out into the atmosphere. And you can actually observe this during day and night cycles. During the day, trees are taking in a bunch of CO2 from the atmosphere, and during the night, you can actually watch them give it off. Now, one important concept is that the larger a tree gets, the more maintenance it takes to keep alive. It’s called maintenance respiration.

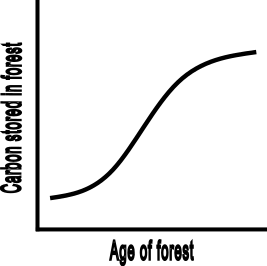

And a very large tree is taking in a lot of CO2, but it’s putting out almost all of that CO2 again just to keep itself alive. It’s not really converting a lot of that CO2 into wood. So very large trees, their growth slows down a lot.

And trees actually follow basically an S-curve as they grow when they’re very small. They’re too small to be accumulating very much carbon. When they get to like a mid-size for a couple of decades, they’re sequestering lots and lots of carbon out of the atmosphere. And then finally, as they get larger and larger, they start to taper off. They’re not able to sequester as much carbon. They’re basically just keeping themselves alive. And of course, most trees do actually senescent die after a few centuries, or even less. Only the most exceptional trees in California generally are able to keep themselves alive for thousands of years.

Now, the same thing actually happens to ecosystems as well. Old growth forests are not taking a lot of carbon out of the atmosphere. Maybe they’re taking a little bit and it’s getting locked away in some soil or rushed down a river. But for the most part, old growth forests are at a steady state system. And this kind of makes sense, right?

If the Amazon rainforest were truly the lungs of the earth taking CO2 out of the atmosphere, then that CO2 would have to go somewhere, right? Over tens of thousands of years, we wouldn’t have a very Amazon forest. We would have an Amazon mountain.

Now, there are a couple of exceptional examples, a couple of forests that do actually permanently sequester CO2 from the atmosphere. Bogs and Arctic tundra are probably the two most notable. And these happen because basically when old trees die, there aren’t any microbes that can actually break down that carbon and release it back into the air.

And so in a bog, when an old tree dies, because the soil acidity is so great, that material just sticks around. And so over tens of thousands of years, bogs will actually turn into small hills. The same thing happens in Arctic tundra. And in the Arctic, ecosystems have been slowly accumulating carbon for thousands and thousands of years.

Of course, this is fairly dangerous because if climate change causes the earth to warm up, and suddenly microbes can then access this carbon, they’re going to release all that CO2 back into the atmosphere. So young trees sequester carbon from the atmosphere, and old trees store a lot of carbon, but aren’t actually taking a bunch of new carbon in. And so it’s very important to preserve old trees, make sure that they don’t get cut down. Otherwise, a lot of carbon will enter the atmosphere. And it’s also very important to plant new trees to undo the climate change damage that we’ve done already.

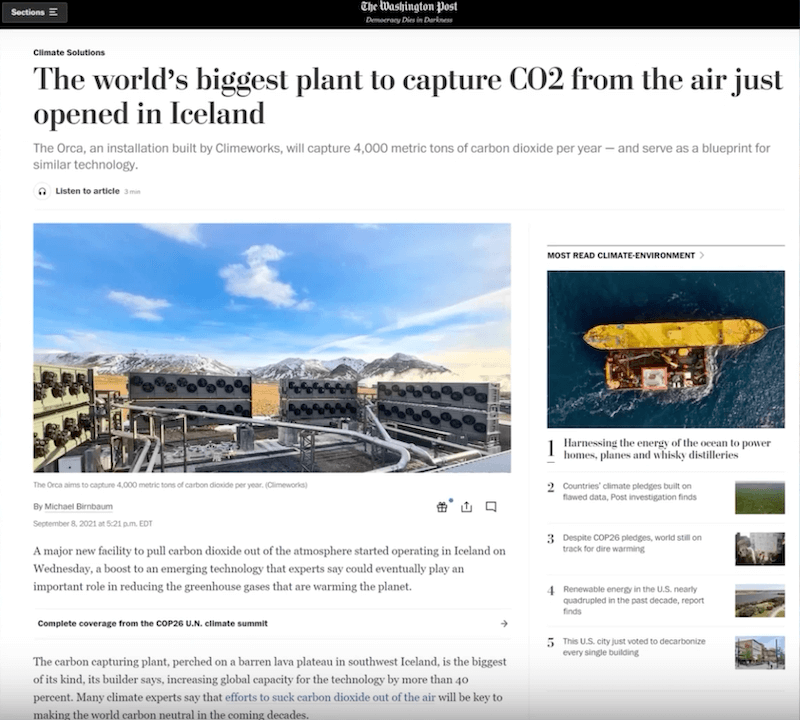

One thing that I’ve always wondered about is how do trees actually compare to other carbon capture technologies? We hear a lot about carbon capture technologies that can take CO2 out of the atmosphere and lock it up. Giant facilities, giant factories that are sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere with fans. And in fact, in September 2021, the world’s largest carbon capture facility came online in Iceland, and it’s able to remove about 4,000 tons of CO2 per year.

So how does this compare to forests? Well, the average Amazon rainforest is able to store about 400 tons of CO2 per hectare.

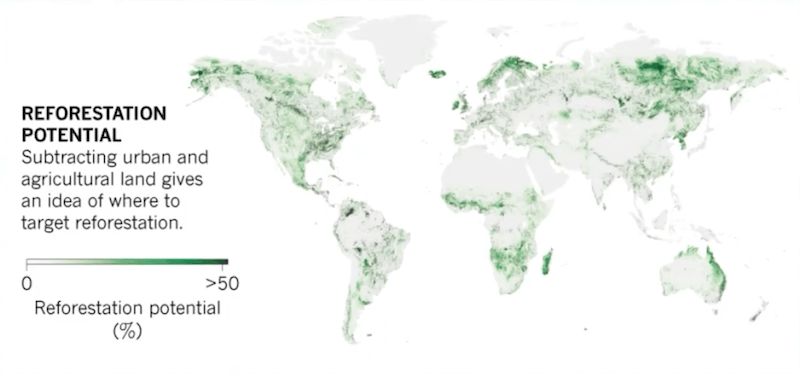

So by preventing about 10 hectares of rainforest from being deforested, we can outdo what the world’s largest carbon capture factory is capable of. And that’s about 25 acres of forest for Americans. And that’s a tiny fraction of the amount of deforestation that takes place on a daily basis. But how does that compare to how trees can actually sequester carbon from the atmosphere? Well, in the reforestation projects that I’ve worked in, a common number that we’ll see is 10 to 15 tons of CO2 per hectare per year. Which means that you’d really only have to plant about 400 hectares of trees in order to outdo the world’s largest CO2 capture facility. 400 hectares is 1,000 acres, which is like a mid-sized farm in the United States.

Now, I’ve worked with carbon projects that exceed 25 tons per hectare per year. So forests are certainly capable of helping us a lot. Scientists quibble about just how much we can count on forests to get us out of climate change. Some people will claim that we can reverse all of the damage done by climate change by just planting more trees. Others will say we can only offset a fraction of the carbon that we put into the atmosphere.

But what we can say for absolute certain is if you plant trees over a small area, you’re going to be sequestering a massive amount of carbon.

It does not take very many trees to reach industrial levels of CO2 offsetting. And so the takeaway that I get out of this is that forests can help us. Forests are really the solution. And when we see these problems with forest carbon offset projects, it’s never got to do with the actual forests. It’s never got to do with nature. It’s always people.

And so the challenge in these forest carbon offset protocols is to draft a set of rules that will keep the people in check. Manage the people who are managing the forests.

So in summary, what have we learned?

- Trees are made of mostly carbon. When you’re wandering around through the forest, you’re basically looking at carbon and hydrogen.

- Young trees sequester a lot of carbon out of the atmosphere. Old trees don’t sequester a lot of carbon from the atmosphere. But they’re storing a lot of carbon in their massive trunks.

- And then finally, if you want to take carbon out of the atmosphere, you can plant young trees. If you want to prevent carbon from going into the atmosphere, you can stop trees from being cut down.

- And if you want to kind of do both, you can take a middle-aged forest that’s slated to be cut down and stop it from being cut down and let those trees grow.

And so those are the bases for the three types of forest carbon projects. Reforestation, avoided deforestation, and improved forest management. And we’ll talk about them more in a later video.